ɬŔď·¬: Researchers closer to gonorrhea vaccine after exhaustive analysis of proteins

In a study of drug-resistant gonorrhea strains historic in its scope, researchers at Oregon State University have pushed closer to a vaccine for gonorrhea and toward understanding why the bacteria that cause the disease are so good at fending off antimicrobial drugs.

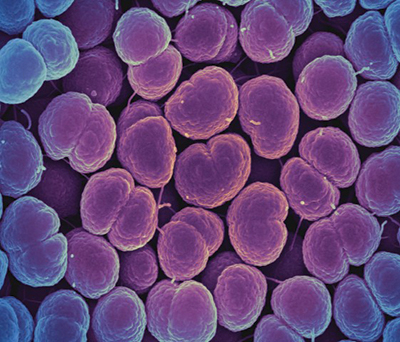

Neisseria gonorrhoeae, the bacterium that causes gonorrhea, is shown here in a scanning electron micrograph.NIAID

Neisseria gonorrhoeae, the bacterium that causes gonorrhea, is shown here in a scanning electron micrograph.NIAID

, published in the journal Molecular & Cellular Proteomics, are especially important since the microbe Neisseria gonorrhoeae is considered a “superbug” because of its resistance to all classes of antibiotics available for treating infections.

Gonorrhea, a sexually transmitted disease that results in 78 million new cases worldwide each year, is highly damaging if untreated or improperly treated. It can lead to endometritis, pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy, epididymitis and infertility.

Babies born to infected mothers are at increased risk of blindness. Up to 50 percent of infected women don’t show any symptoms, but those asymptomatic cases still can lead to severe consequences for the patient’s reproductive health, miscarriage or premature delivery.

, a researcher with the OSU College of Pharmacy and Oregon Health and Science University’s Vaccine and Gene Therapy Institute, helped lead an international collaboration that performed proteomic profiling on 15 gonococcal strains.

Among the isolates in the study were the reference strains maintained by the World Health Organization that show all known profiles of gonococcal antimicrobial resistance.

For each strain, researchers divided the proteins into those found on the cell envelope and those in the cytoplasm. More than 1,600 proteins — 904 from the cell envelopes and 723 from the cytoplasm — were found to be common among all 15 strains, and from those, nine new potential vaccine candidates were identified.

A vaccine works by introducing an “invader” protein known as an antigen that triggers the body’s immune system and subsequently helps it quickly recognize and attack the organism that produced the antigen.

Researchers also found six new proteins that were expressed distinctively in all of the strains, suggesting they’re markers for or play roles in drug resistance and thus might be effective targets for new antimicrobials.

In addition, scientists looked at the connection between bacterial phenotype — the microbes’ observable characteristics and behavior — and the resistance signatures that studying the proteins revealed; they found seven matching phenotype clusters between already-known signatures and the ones uncovered by proteomic analysis.

Together, the findings represent a key step toward new weapons in the fight against a relentless and ever-evolving pathogen.

“We created a reference proteomics databank for researchers looking at gonococcal vaccines and also antimicrobial resistance,” said Sikora, co-corresponding author on the study. “This was the first such large-scale proteomic survey to identify new vaccine candidates and potential resistance signatures. It’s very exciting.”

The findings add new momentum to a vaccine quest that also received a boost in summer 2017, when showed that patients receiving the outer membrane vesicle meningococcal B vaccine to prevent Neisseria meningitis were 30 percent less likely to contract gonorrhea than those who didn’t get the vaccine.

“All previous vaccine trials had failed,” Sikora said.

Gonorrhea and meningococcal meningitis have different means of transmission, and they cause different problems in the body, but their source pathogens are close genetic relatives.

This article is republished from the website.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Mapping fentanyl’s cellular footprint

Using a new imaging method, researchers at State University of New York at Buffalo traced fentanyl’s effects inside brain immune cells, revealing how the drug alters lipid droplets, pointing to new paths for addiction diagnostics.

Designing life’s building blocks with AI

Tanja Kortemme, a professor at the University of California, San Francisco, will discuss her research using computational biology to engineer proteins at the 2026 ASBMB Annual Meeting.

Cholesterol as a novel biomarker for Fragile X syndrome

Researchers in Quebec identified lower levels of a brain cholesterol metabolite, 24-hydroxycholesterol, in patients with fragile X syndrome, a finding that could provide a simple blood-based biomarker for understanding and managing the condition.

How lipid metabolism shapes sperm development

Researchers at Hokkaido University identify the enzyme behind a key lipid in sperm development. The findings reveal how seminolipids shape sperm formation and may inform future diagnostics and treatments for male infertility.

Mass spec method captures proteins in native membranes

Yale scientists developed a mass spec protocol that keeps proteins in their native environment, detects intact protein complexes and tracks drug binding, offering a clearer view of membrane biology.

Laser-assisted cryoEM method preserves protein structure

University of Wisconsin–Madison researchers devised a method that prevents protein compaction during cryoEM prep, restoring natural structure for mass spec studies. The approach could expand high-resolution imaging to more complex protein systems.